June 2022 Update - The Only Game I Ever Replay

What's good, internet?

It has been a longer time that I’d hope for between setting up this mailing list and sending it. The delay is mostly because I have been incredibly busy with work stuff—between the end of the latest Friends at the Table season Sangfielle, wrapping up season 4 of Clone Wars over on A More Civilized Age, a serious and dedicated return to work on an unannounced TTRPG project that I recently started teasing, and uh, you know, also my entire dayjob (we’re hiring!), the calendar has been filled.

Which hasn’t meant that I haven’t made time to guest on various things! I was invited to LudaNarraCon to speak with Citizen Sleeper designer Gareth Damian Martin, and we had a great talk about a game I enjoy quite a bit. I once again joined the Great Gundam Project to talk through the many disappointments of Gundam SEED with Em and Jackson. I joined Michael and Cameron over on Game Study Study Buddies to talk about William J. White’s Tabletop RPG Design in Theory and Practice at the Forge specifically and early 2000s forum culture more broadly. And I swung through to Nextlander to join my old co-workers to chat about uhhhhhhhh the nature of a mech, finding porn in the woods, and being able to consume media for your own joy instead of as the raw material for Content Churn.

It hasn't only been the lack of time keeping me from writing, though. There is also the matter of the anxiety. Just ask anyone who has edited my work before: One of the most common traps I fall into as a writer is the feeling that every new thing I write needs to be, if not perfect, then at least up to some absurdly high, self-appointed standard. On one hand, being a perfectionist has led me to write some stuff I'm very happy with. On the other, it has also left a lot of ideas half-finished and shelved indefinitely. Not a great trade.

This was one of the great things I had to struggle with when shifting from academia to the enthusiast press. One of the earliest lessons that Jeff Gerstmann instilled in me, early in my tenure at Giant Bomb, was to care more about my figurative batting average than my home runs. The big hits would come naturally so long as I was focused on turning out decent thoughts pretty regularly.

So, instead of curling myself over a keyboard late into the night, trying to get water from an over-scheduled stone, I am instead going to finish knocking together some loose thoughts about something extremely predictable:

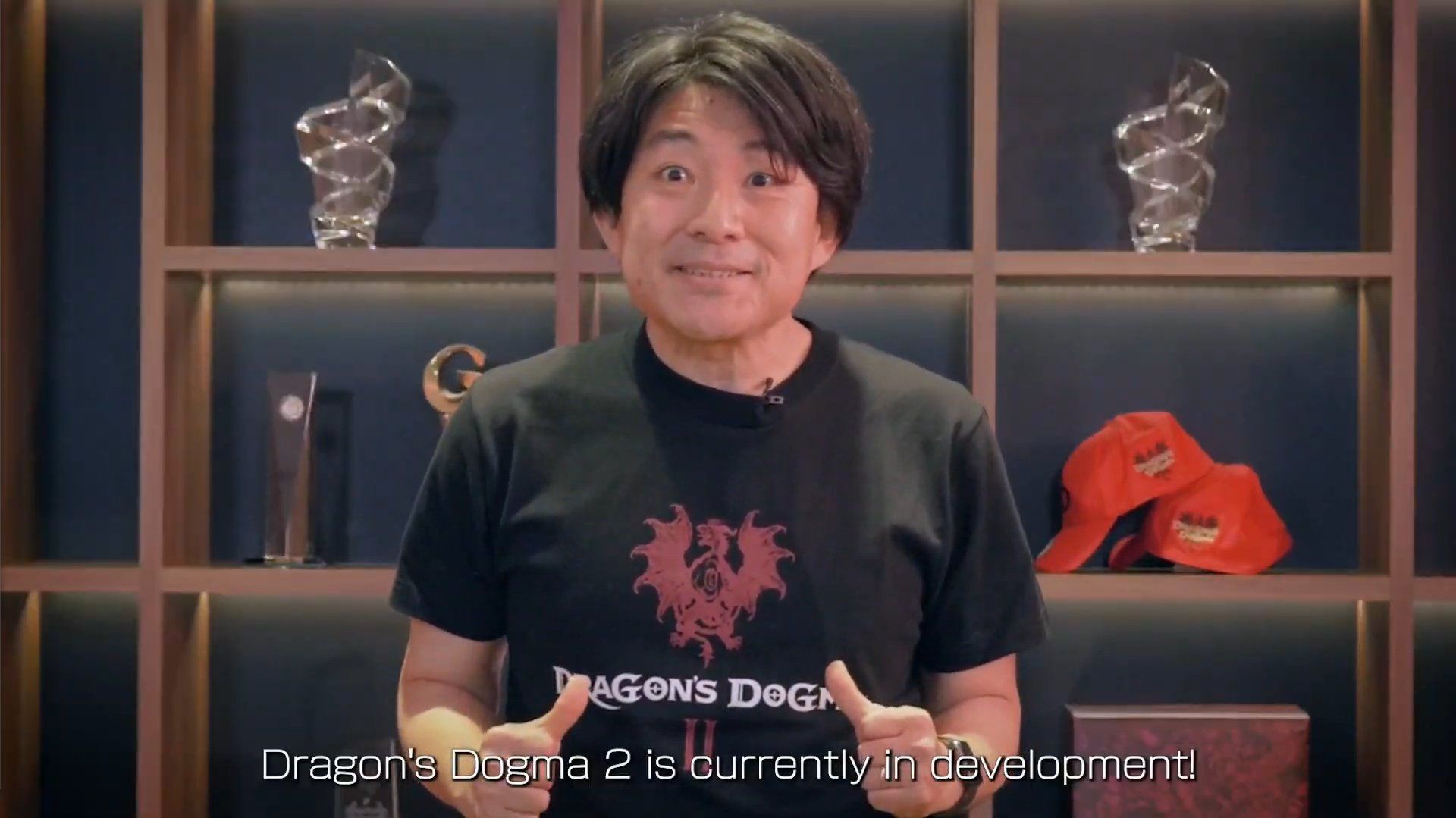

Yeah, yeah, big surprise, I know. (Especially if you already listened to today’s Waypoint Radio).

The funny thing is, I wrote most of what follows over the past few months, as I'd replayed the game to confirm my dark suspcion—that I like it more than Elden Ring. (I do.) I also suspected we’d hit a Dragon’s Dogma 2 announcement for so long that I actually started working on these thoughts a couple of days after I first launched this newsletter, before all that aforementioned schedule implosion happened.

So, inspired by the announcement of a sequel to one of my favorite games of all time, and eager to get past the feeling that I can only post Perfectly Polished Essays, I’ve picked these notes up, given them a slight shine, and posted them below.

This runs long, even for me, and I think it's meandering and unfocused. It is like many of my least favorite things more comprehensive than holistic. But it's also the first time I've written directly about this game instead of using it as a jumping off point for something else. Which, given my long advocacy for it, is sort of remarkable and a good enough excuse to hit publish.

In honesty, though, I think with more time I'd give them a pass to be a little less maudlin. But "this could be better" is exactly the pitfall I'm trying to avoid, and after all, Dragon's Dogma is a pretty melancholic game, so maybe it's fine.

In any case...

I’ve Been Playing It Again

Why is it that Dragon's Dogma is the only game I ever replay?

Okay, this isn't exactly true. There are a handful of others, like the single-sitting duo of Gravity Bone and Thirty Flights of Loving, which always center me and remind me of all the feelings most video games can't pull from me. But where others might replay A Link to the Past, Resident Evil 4, Mass Effect 2, Undertale, or some other highly influential mainstay of "Top 100 games of all time" lists, I return to Dragon's Dogma.

I have even made ill-fated attempts to replay many other games, like Fallout: New Vegas and Final Fantasy Tactics—games I might, on the right day, tell you I like more than Dragon’s Dogma. But the latter is the only one I have replayed to completion multiple times.

It has been a decade since I first knew I wanted to play Dragon's Dogma.

It was Patrick Klepek's Quick Look of the game on Giant Bomb that made me interested in it. (All these years later, it remains surreal to me that I got to add my own Quick Look of the game to the site in my short tenure there.)

After its debut, the press described it as Capcom's action-RPG-take on the discourse-defining Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim. Yes, it would have sharper, more exciting combat design—members of the team had worked on series like Devil May Cry and Monster Hunter. That alone was not a very interesting pitch to me, but now that I had saw it in action, something compelled me. What was it?

Maybe it was the way Patrick’s cursor-like reticle—the distinguishing feature of the Magick Archer class—swept over enemies, marking them as if they were foes in Panzer Dragoon or Rez. [My raw notes bring up this exact sensation no less than four times. The specific skill in question is Hunter’s Bolt, and it rules.]

There's a chance that what drew me to it was the banter of the Pawns, the AI companions that you employ during your quest. Their constant (and now, constantly meme'd) chatter is likely the most polarizing element of the game. Informed by their adventures as hirees in other player's games, they loudly, repeatedly shout the strengths and weaknesses of your current foe, along with some tips for whatever quest you're currently on. In the early game, this leads to lots of repeated material. By the end, they seem to know more than you—something I'll return to later.

Why did this pawn "banter" land for me instead of drive me away?

First, the game's writing localized by Erin Ellis, is the rare example of a script featuring well-used archaic and less-common words, and it features a lot of distinctive cadences for its characters, giving them a special touch that separates them from so many other fantasy NPCs. Second, there's the way it produces a layer of simulated camradery. Even when roughly roughly done, this has always appealed to me. Wingmen, roommates, bickering space colonists—one of the easiest ways then as now to make me interested in a game is to say "hey, we've got some systems-driven mechanic to fill the dead air and mimic co-presence."

(This might not be too ar from the dev team's goal: In the 10 Year Anniversary Message, Itsuno notes that he wanted to evoke the sense of playing a multiplayer game but in a single player experience. Does it do that? Maybe. Maybe it does something else. One thing it absolute does is abhor silence. And when it is 2 or 3 or 4 AM, and I am unable to sleep, and so I boot it up again on Switch, and start over one more time, I do too.)

Looking back on it now, maybe Patrick's QL was so entrancing to me because he happened to pick one of the most iconic sections of the game to play. He pursues the Griffin through the Windworn Valley to the Bluemoon Tower, fighting through a bandit’s den and pushing through the wind itself until he has a climactic confrontation with the mythical beast.

The Windworn Valley. The Bluemoon Tower. The Griffin. Its most powerful mythical beasts are singular creatures, terrorizing the countryside. Its locations are monuments to a past you seem to understand without reading a single Compendium Entry. This is the mode that Dogma operates under until, in its endgame and expansion Dark Arisen, it spins back on itself.

Dogma's story was unlikely what drew me to it, but it is certainly must be at least part of why I return to it.

In brief: For the first time in generations, a dragon has come to the land of Gransys, bringing with it creatures of myth and legend. The player, the Arisen, has had their heart taken from them by the dragon. On their way to reclaim it, they learn that the world’s pathways, already beset by bandit clans, ferocious animals, and the ever-present mundane dangers of distance and darkness, are now filled with the storybook monsters. Those sworn to defend Gransys—dukes, dignitaries, and common soldiers—are corrupt, craven and capricious.

So, you step in. Aiding you on your task to remedy this danger are Pawns, the aforementioned AI-controlled companions who appear as humans, walk between realities (different player campaigns), and are seemingly limited in agency. Unraveling their role and capacity is, in some ways, the central mystery of the game.

People say that Dogma has an “okay” or “serviceable” or “fine” story a lot. I think it’s quite a bit better than that, especially in the “endgame,” where the world state shifts dramatically and with the development that comes in Dark Arisen. Here’s how (spoilers on this link, but not in the quote below) Cameron Kunzelman describes it:

Critic Matt Lees once said that Dragon’s Dogma is “hobbity as all fuck,” meaning that its familiar cadence of chosen ones, dragons, dukes, ogres, soldiers, forts, and sorcerers are all part and parcel of the traditional fantasy puzzle. Similarly, the idea that you are an important person with more skills and better capabilities than your average dirt farmer is the basic structure of role-playing video games. Like Dark Souls only a year earlier, Dragon’s Dogma uses the common anchor of the special protagonist to make the player feel settled in a world they think they know. Then they pull the rug out from under you.

So: A story that plays with expectations. A layer of exactly the right sort of faux-sociality. A few unique skills. Is that enough to explain my constant return to this game? Is it that simple, why I have over 300 hours in this game across five platforms? Does it explain why, when my depression rumbles loudest, I find some refuge—though not relief—in returning to Gransys.

I don’t know. I don't think so. But then, I've only been describing things you can see in someone else's playthrough, not things you can feel in your own. So let me keep describing it—let me share my notes, some finished, some rough—and see if anything shakes out.

See That Mountain?

It's undeniable. Dogma is definitely a “see that mountain, you can go there” game. But, whatever early previews and marketing said, it has very little in common with the Elder Scrolls games with which it was often compared.

This is not a game interested in bombarding players with lore. There are supernatural realms, factions, and NPCs in Gransys, but they're iconic—not in the promotional sense, in that they are archetypal and familiar, and they gain their depth not from in-world books you read, but from encountering them directly. This is not a game not asking you to read compendium entries about distant lands. It is asking you to explore (and learn) the geography of a world.

In Dogma’s base campaign, the process of internalizing Gransys is stretched over dozens of hours. Learning the mountain passes, the coastal valleys, the caves that cut between east and west. In the expansion, Dark Arisen’s Bitterblack Isle, this sense learning still takes hours, but the geography is contracted into a dungeon as magnetic as any I’ve ever explored in a video game.

- There is a notorious, early-game quest about finding a "A fine purse fashioned from whiteth snakeskin, likely dropped by accident.” The purse is somewhere along a long, winding river that runs east from the mountains to the sea.

For years, players groaned about this quest, because the purse could appear at any one of a few dozen loot points, with a very low chance of spawning.

A few years ago, someone figured out the one place it always spawns. An act of collective mapping. - Nevertheless, I always check all the other spots first.

Dogma is deeply interested in embodiment. I do not mean this as a synonym for “immersion” in the Deus Ex-, Far Cry 2-sense. I never feel like I’m there when I play Dragon’s Dogma. But that isn’t what it’s trying to do.

Instead: I mean that Dogma offers a wide range of physical sensations, separated across skills and classes.

- The aforementioned Magick Archer wields a special bow, but its real weapon is the big, circular reticle need only contain or pass over a target. Contrasted by the physical bow classes and the taut sensation of pulling and holding a string.

- Biting Wind, a skill for dagger-wielding classes, reads: “Dashes past the target with blades extended, delivering slashes that can be followed with further attacks on contact." It feels like taking the cap off a pen and scratching out something you wish you hadn’t written.

- There are so many small timing windows in this, though none as punishing as something like the parrying in Sekiro. I can call them up in my mind, waiting to deliver the Thunder Riposte of the Mystic Knight, or to the exact press-hold-release of Magickal Gleam—an illuminating arrow that, in most other games, would never find its way into your limited skill arsenal. But in nights as dark as this? Well.

- The GIF (not mine, unlike the others in this piece)

Is that it? Am I closer? Yes, closer. I can feel the controller in my hands as I type this now. I can recall the exact sensation of the double jump, leaping from rooftop to rooftop like an ad hoc platformer, or slamming R2 to grasp onto the Cyclops' back as it turns to face my party. The perfect counter timing of the Assassin's Easy Kill.

Closer, but not there. Keep describing. Go broader. Find a metaphor.

I like Dragon's Dogma the way I like coffee, not cake.

I don't mean that it is addictive (although, one wonders, seeing how I write about it). Instead:

It is a staple, not a treat.

- Despite Dogma’s pedigree, it is not built like a DMC game—meant to be consumed in a short matter of hours, filled with astonishing set pieces and blistering combat design. And, to ring this bell again, it is not paced like Skyrim either: You never settle into that familiar Elder Scrolls mode of selecting the nearest quest, clearing it, and then repeating.

- I spend most of my time in Dogma walking from place to place. Even in Dark Arisen, which greatly increased the ability for a player to fast travel, the game is defined as much by the walk up the hill as much as the battle you enter when you reach its peak.

- In combat, exploration, and preparation, this is a game where you move with discrete purpose. And these scaffold together perfectly.

- In combat, a balance of team composition, limited skill slots, and resource management means that every fight requires attention. Not because you may die—though, especially early, that too—but because it may cost you more resources than you’d like to spend.

- This is important because the first thing you learn as an explorer of Gransys is how important managing your resources is. Dogma is one of the only major console releases that has made me fear the dark, but that is only the start. Mages can heal you up, but never to your total max health, which ticks down with every hit you take—so you rely on potions regularly. Add to that the actual utility that damage boosting items, special arrows, and other curatives provide, and it is the rare game that I enjoy crafting in.

- Part of the reason why I enjoy crafting is also why preparation stands out. The menus might be cumbersome, but the sounds they make as you scroll around and make choices are as good as anything in video games. More important, Dogma takes the way that you begin a hunt in Monster Hunter and makes it more organic. This is a game where you run your errands, you back your bags, and you set off.

It is a familiar taste concerned with soft distinctions.

- Despite eventually subverting the fantasy conventions it is draped in, it cares a lot about capturing what is attractive about those ideas to begin with. Like Record of Lodoss War or Dungeon Meshi, it is unabashedly clear in its inspirations, but never feels like a dull or lazy copy. As the world comes into focus, it feels almost like filling out a Picross puzzle and beginning to recognize a shape. Aha, the valorized knight with a dark secret!

It is like coffee in that it is both mundane and ritualistic.

- Take everything I said above about preparation but extend it across a game just long enough to settle into again.

- Starting a new run of Dogma for me is like a hand gently lifting the spoon with the ground coffee. Reaching the capital city of Gran Soren, unlocking the second set of Vocations, slowly filling in the gaps of the map of Gransys—the milk spirals as I twirl the spoon.

- I enter the Wyrm Hunt, the de facto start of the mid-game, a collection of classic fantasy quests (hunt down the cult, decipher the ancient quest, things of that nature). As I scroll between the option of which to take on first this time, it feels like lifting a mug, dark aroma in the air. Ah, the Watergod’s Altar first, I think.

It is like coffee because you can adjust it to meet your tastes, and learning how to do that is a rewarding process.

- I cannot oversell how distinct each class feels. There is no magic class in video games like the Sorcerer (and no mechanic quite like Spell Syncing). Even among seemingly similar classes (like the bow and dagger wielding Ranger, Strider, and Assassin), there is a great deal of gamefeel difference.

(For the record: Magick Archer remains my favorite Vocation, maybe my favorite class in video games) - It is entirely viable to pick a class and play the entire game through as that class. But Dogma rewards both planning and experimentation. Each class has special Augments to unlock, passive buffs that you can apply regardless of what class you are currently playing as.

(As I write those words, and I start involuntarily thinking about combining Augments in different ways, I can—and I mean this literally, I can literally—feel something like a gentle fingernail running from the mid-front right of my brain backwards, curving under my skull, landing somewhere just right of my spine.) - In Dark Arisen, the game shifts into something almost run-based, where you dive again and again into a dungeon with rooms that shift enemy composition as you return. As you do, you come back up with loot ready to be identified, including some items with randomized stats or abilities. Suddenly, linear progression goes wide and you are making decisions about style more than power.

Is that it? Familiar beyond touch, to the realm of metaphorical taste? The subtle imprints of an interface and all its requisite chirps? The way a game can change the subjective experience of time? Not enough. Still missing something. Somehow I have left out how it makes me feel.

Doing Maintenance

Years ago I wrote about how the first Destiny ws something like a maintenance game for me:

I wasn't "disappearing" into Destiny, the way I did when Skyrim or Fallout: New Vegas drew me into their worlds. It wasn't "junk food gaming," a phrase I tend to reserve for games that are empty time killers or else are pleasurable for their cheesiness or baseness. It was more positive than that, a sort of quiet self-care enabled by the clean repetition of enjoyable motions. When I finished playing Destiny on any given day (or late night), I left it feeling better.

Five years later, it’s clear that Dragon’s Dogma does this for me better and more often than anything else. Have I returned to Destiny? Sure, occasionally. I play the new content and I move on. I do not “return.”

- I wrote many of these notes on a bus to New Jersey on May 24th, 2022. When the news broke, I found myself grateful I had loaded Dragon’s Dogma: Dark Arisen onto my Steam Deck. I did not find the time to play in the days that followed—spent with family, quietly and gratefully. But I felt calmer having it with me.

Here is a note I made that day but did not finish, and cannot find the words for now:

- I replay it yearly when I feel like this. Comfort, safety, ease, challenge, inspiration. I fold it around me, a parka, a blanket. I lay it down like a towel on the beach. I hang it from the wall, a tapestry.

- I don’t know why it feels like cloth, but it does.

That said, this feature of playing the game—something I associated with “self-care” years ago, a term I’m less willing to throw around now—is a feature available to me because of its qualities (and because of my history with it), not a quality in-and-of-itself. I wasn’t calmed when I first played it, after all.

So, something else, something beyond the way I feel, something it does. A way it makes me think about the world.

What If?

Dragon's Dogma feels weird, but in a way that busts “feels weird” open.

Each time I play I feel a reminder that other games could feel like this, but feel like Something Else instead.

It's not even that they feel like The Last of Us, but that they feel like Third Person Stealth Action Games. Not that they feel like Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare, but First Person Shooters. These are categories we deploy as if it they are natural—as if any categorization is as simple as that.

It does not have the lock-on or auto-facing camera of a Dark Souls or Zelda game. It spreads fundamental movement and combat features—double jumps, parries, dodge rolls—across different classes. Magic spells are targeted slowly, crawling out across the ground like an RTS cursor while you wait for them to charge.

What feels "natural" (even in an interactive medium, where a controller fits just so in your hands) is a construct of history and economics and culture as much as ergonomic truth.

- Dragon’s Dogma doesn’t feel natural to me, it feels as if it could have felt natural. It opens a door to a possible world where we played a dozen other games that felt like this. That world is possible!

- (Of course, Dark Souls was itself another "feels weird" game that did end up shifting the "natural feeling" of play, effectively inventing a new sub-genre. Would I be a happier person if there were Lords of the Fallen or The Surge style games, inspired by Dogma? Not especially. But it's hard not to wonder what the teams behind Nioh, Ashen, or Jedi: Fallen Order might have made if they'd tried to tackle a Dragon's Dogma-alike.)

Eternal Return

Irony of ironies, Dragon’s Dogma itself does not, I think, believe that other worlds are possible.

- The most loved song among the greater Dogma fanbase is probably "Into Free" by B'z, the original release's opening theme. That's understandable—the slow piano builds to an absolute banger of an anime OP. It's probably in my top five, but it doesn't touch "Coils of Light," the climactic theme of Dark Arisen which leverages elements of other tracks throughout the game, including the dreary opener, "Eternal Return." The thematic centrality of that Nietzschean concept is an important reason to put Dogma in conversation with the Dark Souls games, and why I'm grateful that Cameron did that in the aforementioned article. Again, spoilers, but worth reading.

- (Of course, the best song in Dogma could never be something you hear in the game's grand opening or climactic close. It has to be something that is part of the mundane ritual of the game. For my money it's "End of the Struggle," which plays whenever an unscripted boss fight begins to turn your way and you near success. Lots of games have dynamic music, very few punctuate this particular beat with such splendor.)

My notes begin to crumble here, becoming a list of things that Dragon’s Dogma believes are unavoidable:

- Corrupt, glory-seeking leaders

- Nihilism and fear from those confronted by their own agency

- Love and compulsion and camaraderie–and their end.

- The familiar is a dagger whose hilt is a blade too.

- The cursed cynicism of the preparatory fantasy, which repeats too. When you prepare for the end of the world, you invite the world to end. (And by inviting in an apocalyptic world, you never free yourself from suffering).

- Peace becomes be itchy and uncomfortable for those with the power to have brought it into being.

In these ways, Dogma is actually quite a bit like doom-scrolling through Twitter, even though I often play it to prevent me from doing just that.

[From here, the bullet points in my notes continue, but are distracted by fear of missing the landing.]

- Still not sure this is anything.

- Maybe a "together, these things combine" type ending? Idk, that's a pretty weak close.

- Find a place to link to both Dia's and Janine's LP of the game, especially given that I was on both of them at various points.

- Wow was the anime disappointing. A huge miss on what makes the storytelling in the game great. It was cool to see a Pawn using Magick Archer though, and I wonder if those two side characters were teasing possible sequel Vocations...

- Could restart and do an Assassin run without Pawns, see if that changes anything?

- It is a mistake to try to find a single reason for this or to frame this piece around that, ughhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh

- Love is not a choice, it is a chain.

- It is a pull and a constraint, something we can choose how to operate under the influence of, but rarely have the means to free ourselves from at will.

When I love a being and I desire it, I include in my judgment the presumption that the entire world ought to love and desire this being, even though I know very well that this is not the case. Desire, in this case, is not of the order of the drive. Desire universalizes its objects; the drive, on the other hand, tends toward the consumption of an object. The latter does not include autouniversalization: desire is to the drive what the beautiful is to that which is merely agreeable.

We are living in a time of lovelessness (désamour): the time of a libidinal economy that is constituted in such a way that, with capitalism having put desire at the center of its energy, this economy has led to the ruin of desire, to the unchaining of its drives, and to the liquidation of philia and more generally of this love that the noetic souls have for each other and for the objects of their world.

-Bernard Stiegler, "The Proletarianization of Sensibility"

- Insofar as I love Dragon's Dogma, it is a waste of time to look for a single key—I am wrapped up by it, not by a single metal rope, but by dozens. The way it feels to break into a sprint. Locked. The voice of the Blacksmith—masterworks all. Locked. The sinking realization that I dropped all my healing items into storage, and have only whatever I scavenged here, deep into the shadowy isle. Locked. The escort quests—I hated these once, and now they are a pleasing punctuation in the ritual, the last thing I do before advancing to the next stage of the game's campaign. Locked.

- (Is this a pretentious way of saying that it has 10s in graphics, sound, AND gameplay? Yes, except that it disposes with the idea that any rating could last the test of time. Hearts change. You cannot "weight" the score of something you love, because you will always find some new connection between you and it that you had not noticed before.)

- Nevertheless some links may grip more tightly than others.

End of the Page

Sometimes as I write a piece, I cut thoughts from higher up in an outline and paste them together at the bottom, hoping they'll cohere into something eventually.

That is why, in this case, the very last set of notes I have is about an unresolved thematic question. It’s a big one: What does Dragon’s Dogma think a person is? These notes don’t lead to a solution, but I’d like it if you read them and think about them—especially as you next play this game yourself.

There is an edge to personhood in this game, and I mean that there are both boundaries and that those boundaries can cut.

I think Dogma intends to include three type sof people, but I suspect it actually includes more.

There are Humans, presumably like you and me. We can't do much.

- In Dragon’s Dogma, Humans are hard to pin down as individuals. The most loyal of us find circumstances where we’ll choose to betray someone. The most world-weary retain some sentimentality. We always surprise. And, as a collective category of beings, there is great diversity. Total us all up and you’ll find no two people exactly alike. Yet we are all of a kind. We all have needs and desires. “Human” is a broad and ill defined category, and this is a feature not a bug.

- With rare exception (like Reynard, a traveling merchant, and Steffen, who takes part in a scripted boss fight) Humans largely stick to wandering around in circles in a single place.

- Sometimes you kill them with little meaningful consequence.

- Humans have things that need doing that they cannot do. They need you to help them find places to live. They need you to bring back large stone tablets lost in ancient ruins. They need you to do them the honor of a duel. They need you to find their missing purse. Without exception, they cannot advance these needs on their own.

There are Monsters, many of whom wear Person-like faces or speak in understandable tongue.

- In most ways, they are like Humans—remaining in one place, without the ability to move the world forward—except you don't do their chores and you always kill them without consequence.

- Some speak to you in their own language, others in yours. The most powerful use language as a weapon, in a literal sense.

- Dragon's Dogma does spends a lot of time very obviously complicating what a person is, where Human, Arisen, and Pawn collide, overlap, and bounce off of one another. It does the same for Monster, but (partly because it wants "monster" to be the category its worse less directly.

- "Monster" as a category of person may need to be subdivided. Dragons are (predictably) distinct in how they act, where they come from, and the voice with which they speak.

- It wants "monster" to be a category that its worst human characters have affinity towards. See: The Duke's final sequences, the facial disfiguration of Elysion, the haunted aura of Salomet.

There is the Arisen, the player character. The unique locus of momentum. Marked by agency and violence, but not alone in that.

- Even setting aside some basic video game protagonist qualities (like “the game’s plot will wait for you to trigger it), the Arisen is a special type of Person. Why?

- Unlike NPC Humans, the Arisen can grow stronger. To do that, though, they must rely on others. You need innkeepers to learn new skills and combine items for you. You need Caxton, masterwork blacksmith, to improve your gear.

- The Arisen is near-silent in a game known for its constant banter.

- Mechanically, while many Humans can fight, only the Arisen has access to nine distinct Vocations, granting them a huge range of violent expressivity that goes beyond anything that anyone else has.

- Narratively: The Arisen can walk around without a heart beating in their chest. Read the metaphor however you want.

There is the Pawn, a category of person fundamentally separate from Human (even though the game narratively wants to blur this distinction). Here are some things that make Pawns distinct from Humans:

- Narratively, Pawns are treated as persons-unto-themselves, distinct and worthy. Yet the game also enshrines the idea of a pawn earning humanity as something special, rare, and beautiful—even in instances where it is sad.

- "Pawn" as narrative category expands beyond "Pawn" as gameplay category: They exist not only as your AI companions, but also as Human-like, quest-giving NPCs who stick in one place, as rare but powerful Monsters, and perhaps they cross over with Arisen in unexpected ways, as well.

- Hired Pawns always follow the Arisen (or take the road in front of them, depending on their inclinations). Unhired pawns walk the major roads, waiting to be recruited. They voice approval when they are chosen, and narratively this desire to serve and help the Arisen is repeated often.

- Pawns learn from how you play, adopting your behaviors and habits, even the bad ones like looting in the middle of combat.

- Pawns can be disciplined, sat down in the dedicated "Knowledge Chair," where a player can tell them to speak and act differently.

- Pawns learn from other players. When a Pawn is hired and brought into another game, they pick up clues about enemy weaknesses, quest steps, and the places of Gransys. They can also learn some of these through the Arisen's use of a knowledge scroll.

- In so far as "knowledge" leads to "action," then Pawns demonstrate that they can know more about the world than the player. Because of the aforementioned Pawn hiring system, Pawns will often attack with the right element or shout about how the player should be fighting. In the menu screens, it often tells you that your Pawn knows some piece of information about an enemy type you've never met.

- How rare is this? In a game so commonly described through its many ways of disempowering the player—its dark nights, its demanding resource management, its equation of the heroic and the apocalyptic—why do so few call attention to the fact that the Pawn is the rare "AI Helper" who can know (in their own way) and do things (like touch the worlds of other real-life humans) that the player cannot? This seems key.

- What thematic work is done by this hypothetical being, the natural servant?

- They are ever-faithful in something quite unlike "friendship" in every way except for proximity and devotion

- They are uncomfortably flexible in relation. You sometimes recruit a pawn for a matter of mintues, letting them die and replacing them with little regard. But some pawns you learn about are treated as children, and others become lovers of their Arisen, or something somehow even closer.

- At the same time as they are diminished and used and dehumanizaed, they are also the ultimate embodiment of change in a world that argues that such a thing is the radical, desirable, and impossible.

- Should we pity the Pawn or be envious of them?

- If a Pawn can become a Human or a Monster, could we one day too?

"Captain Ahab is engaged in an irresistible becoming-whale with Moby-Dick; but the animal, Moby-Dick, must simultaneously become an unbearable pure whiteness, a shimmering pure white wall, a silver thread that stretches out and supples up "like" a girl, or twists like a whip, or stands like a rampart."

Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus